A Wrong Turn with a Long Shadow

We weren’t looking for a border.

Dusty and I were trying to find a park—one she remembered visiting years ago with her mom, back when memories still came with voices attached to them. The GPS sent us to an RV resort that definitely wasn’t it. But instead of a dead end, it delivered us to something unexpected: a historical marker tucked quietly along the Chattahoochee River.

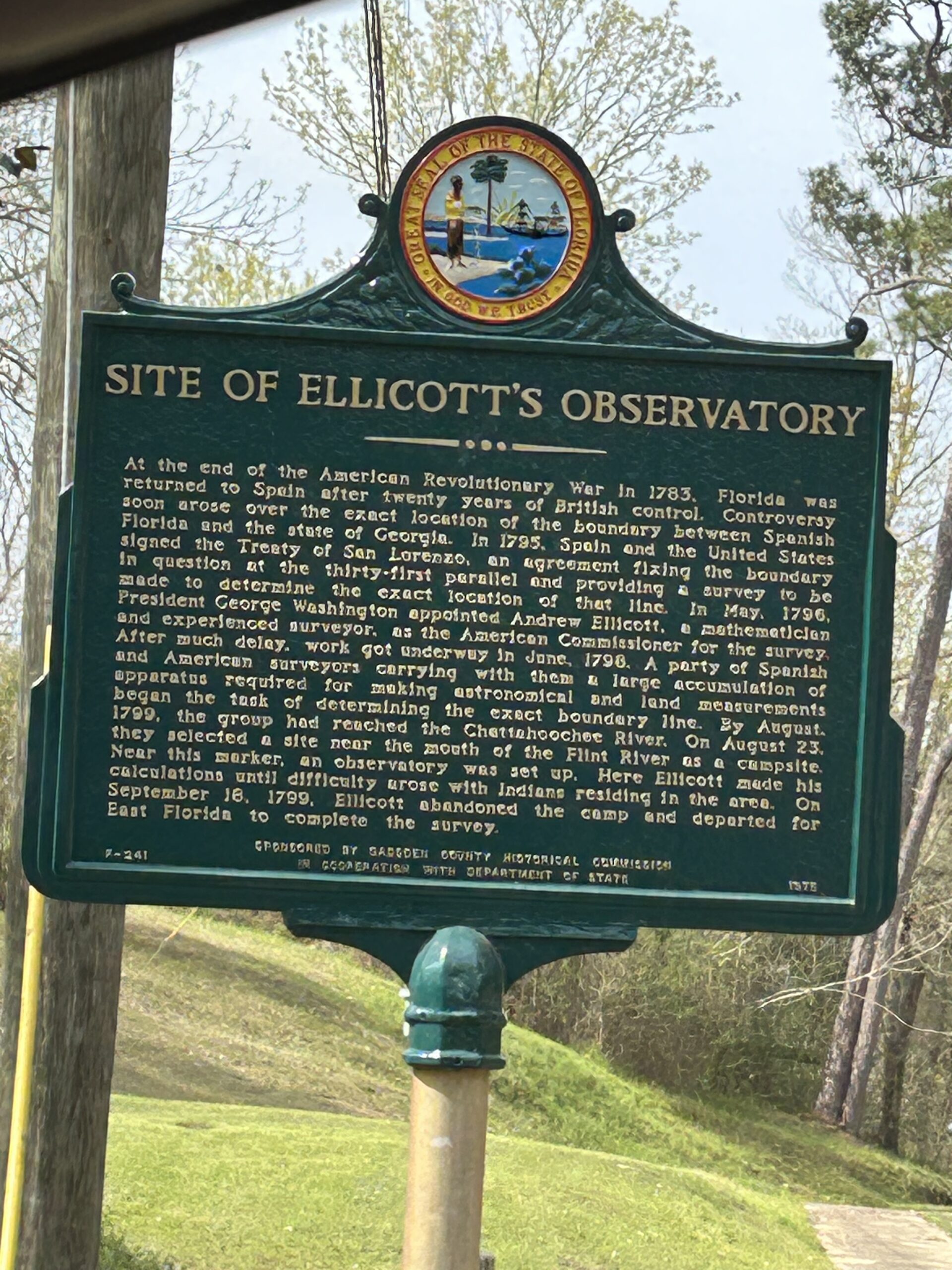

Ellicott’s Observatory.

We stopped. We read. And just like that, the day shifted.

What started as a detour turned into one of those Travel Made Personal moments—the kind where history steps out of the woods, taps you on the shoulder, and says, “You might want to hear this.”

The Chattahoochee River has long been more than a scenic boundary—it’s been a working artery of power, trade, and control, something we explored further during our visit to the Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam, where engineering and history converge on the waterline.

When America Needed a Line

In the 1790s, the United States was still figuring out what it was—and where it ended.

Spain technically controlled much of the territory south of Georgia and the Mississippi Territory, but control on paper didn’t always translate to control on the ground. Tensions simmered. Borders blurred. Forts sat in awkward places.

The solution came in 1795 with the Treaty of San Lorenzo, better known as the Pinckney Treaty. It declared that the southern boundary of the United States would run along the 31st parallel of latitude.

Simple idea. Complicated execution.

To make the line real, President George Washington needed someone who could argue with empires using math instead of muskets.

He chose Andrew Ellicott.

Andrew Ellicott and the Stars Above the Swamps

Ellicott was already respected for his precision. He had helped extend the Mason–Dixon Line and surveyed vast stretches of the young nation. But this assignment was different.

His task: lead an expedition to mark the 31st parallel from the Mississippi River east to the Chattahoochee River.

No satellites.

No GPS.

Just telescopes, astronomical clocks, and the stars themselves.

The expedition was supposed to be a joint effort with Spanish commissioners. In reality, cooperation evaporated once Spanish officials realized the new line would place some of their forts firmly on American soil.

Progress slowed. Supplies vanished. Illness spread. Politics interfered.

And then Ellicott discovered something worse.

Eight Thousand Feet of Truth

Midway through the survey, Ellicott’s celestial observations revealed that an earlier estimate of the boundary line was wrong—by more than 8,500 feet.

In the wilderness.

Under pressure.

With international eyes watching.

Ellicott corrected the line anyway.

That decision required revising months of work, re-establishing reference points, and enduring even more resistance. Along the way, temporary observatories were constructed—like the one marked here—where Ellicott paused to read the heavens and anchor the border to something no empire could argue with.

The boundary itself was marked mile by mile with earthen mounds, each one a quiet declaration: this line matters.

The Stone That Made It Real

In 1799, the work culminated with the placement of Ellicott’s Stone near the Mobile River.

On one side:

U.S. Lat. 31 1799

On the other:

Dominio de S.M. CAROLUS IV. Lat. 31 1799

The treaty created the border.

The stone proved it.

From that single reference point, surveyors mapped vast portions of Alabama and Mississippi using what became known as the St. Stephens Meridian. Counties, towns, and property lines followed—shaping the South as we know it today.

All because one man trusted the stars and refused to move the line to make life easier.

Once the boundary was settled, the federal government moved quickly to establish a stronger presence in the region—something that becomes tangible when you visit the U.S. Arsenal Officer’s Headquarters, a reminder that lines on maps are often followed by boots on the ground.

Standing There Now

Today, Ellicott’s Observatory isn’t a grand structure. It’s a marker. A pause. A reminder.

Standing there—on a day that already carried its own quiet weight—we were reminded that history doesn’t always announce itself. Sometimes it waits at the end of a wrong turn, patient as a stone, hoping someone will stop long enough to listen.

We came looking for a memory.

We found a border.

After reading the marker, we wandered down toward the river itself—an unplanned pause at River Landing Park, where the Chattahoochee’s quieter beauty hides layers of steamboat history and forgotten crossings.

📍 Travel Notes

- Location: Ellicott’s Observatory Historical Marker, near the Chattahoochee River

- Best Time to Visit: Daylight hours; pair with a walk along the river or a stop at Victory Bridge

- Why It Matters: This is one of the places where America’s southern boundary was calculated using astronomy—not force

Echo’s Corner 👁️🗨️

Ellicott’s work didn’t just settle a border dispute—it proved that scientific precision could hold its own against political pressure. In a time when maps were arguments, the stars were the most impartial witnesses anyone could call.

Some stories don’t announce themselves.

They wait at the end of a wrong turn.

If you love forgotten history, quiet markers, and the moments when travel turns personal, come walk the backroads with us. Join the Travel Made Personal newsletter for stories drawn from maps, memory, and the spaces in between.

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.